Curiosity and the ability to look at the world from fresh perspectives are a driving force for innovation and discovery. Three inventors working at Tampere University share the stories behind their inventions.

For most of us, a tattered plastic bag is ugly and worthless, but inventors see the world differently. A scrap of plastic attached to the door of a woodshed and swinging in the wind is an important indicator for Ilmari Tamminen.

“It shows me that the air is moving,” Tamminen says.

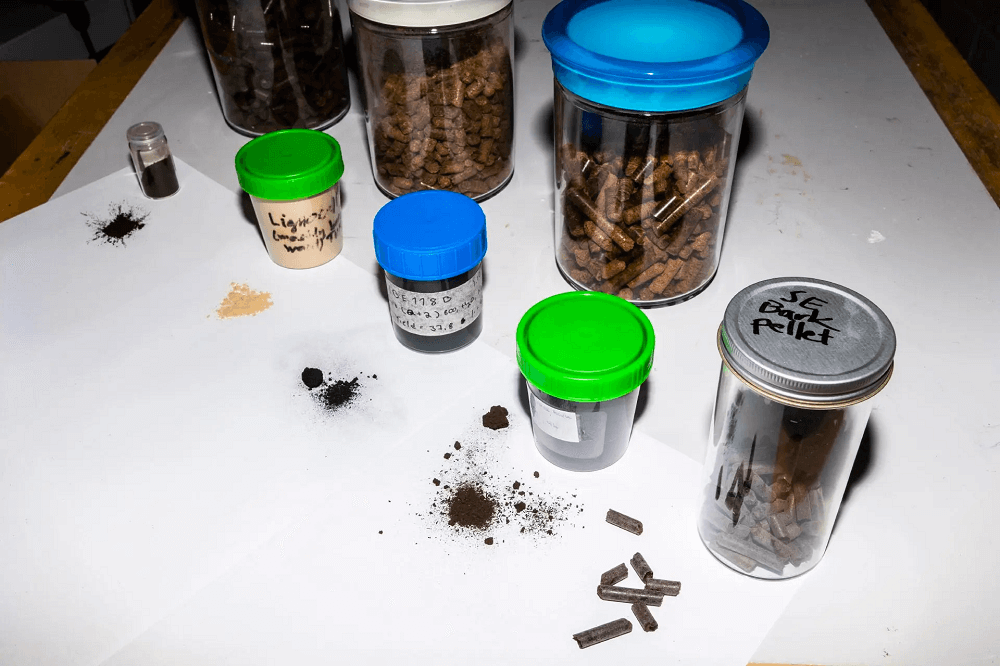

Tamminen studies staining and imaging techniques in the Faculty of Medicine and Health Technology at Tampere University. In lay terminology, his work entails dying cells and tissues so that their internal structures can be visualized using biomedical imaging.

“To put in another way, I am trying to figure out how to tap into the full potential of run-of-the-mill X-ray machines,” Tamminen describes.

Tamminen’s scientific creativity comes to life in a laboratory, but he is also excited about his homemade inventions. The family heats their home with wood and, since wood must be properly seasoned for it to burn well, Tamminen came up with an ingenious workaround to accelerate the drying process.

“I switched the hinges to the other side and wedged the door open at a specific angle. Now the door catches the wind blowing from a clearing and speeds up drying.”

The ingenuity of this invention lies in the simplicity of the idea. The way inventors approach the world around them is what sets them apart from the rest of us: when they see problems, their mind begins to see solutions.

“The key is having plenty of ideas but not falling in love with any of them. Ideas must be coolly assessed to determine what works and what does not. It is important to write down one’s thoughts and carry out bold experiments, because few of us will hit the jackpot right away, at least when working on large-scale projects,” Tamminen says.

Matching a problem with a solution

In 2020, Industry Professor Tero Joronen was presented with Tampere University’s Inventor of the Year Award. Joronen has always wanted to look at the world with fresh eyes. His inquiring mind has resulted in a number of patents – last year alone, Joronen invented or co-invented ten inventions. Joronen has come up with most of his inventions while working in industry, Valmet to be specific, and the rest in academia.

“The first step is to identify a problem and describe it in clear and simple terms. A complex problem requires a complex solution,” Joronen points out.

Joronen is naturally curious and more or less constantly looking for ways to improve things. While most of his inventions are in the field of heavy industry, inventing is also a hobby for Joronen. His home is full of small labour-saving innovations.

“The joy of discovery fuels my passion for inventing. I get a kick out of creating something new. And I have always had a lively imagination,” he muses.

Every other application results in a patent

In total, 1,685 patent applications were submitted in Finland in 2020, the largest number in the past five years. The vast majority of patent applications are filed by large industrial companies, such as Valmet where Joronen works.

There are two reasons: these companies make R&D a priority and have money to spend on it. Turning an idea into a patent costs a minimum of €10,000 in Finland but applying for patent protection abroad will multiply the costs. Patent agent and attorney fees are the largest single item of expenditure.

“The number of patent applications seems to be levelling off after years of steady decline, but why this is happening is anyone’s guess. Of all applications filed, roughly 50% result in a patent,” says Olli Sievänen, head patent advisor in the Finnish Patent and Registration Office.

Scientific knowledge and expertise both spark and steer innovation.

Creativity is an important quality for engineers, too

Pasi Keinänen, project manager in the Faculty of Engineering and Natural Sciences at Tampere University, has a brain that looks at problems but sees opportunities. When Keinänen once again hoovered up pieces of his children’s Lego, a pedagogically oriented father might have reminded his children to tidy up after themselves. Being an accomplished inventor in the field of nanotechnology and having worked as an IP advisor at Tampere University, Keinänen had a different approach: he modified the vacuum cleaner. By manipulating airflow, Keinänen was able to separate Lego from dust, and vacuuming is now a breeze. Physicists know how this is done. We non-physicists might not, no matter how hard we try (Keinänen tried to explain it – to no avail).

“Scientific knowledge and expertise both spark and steer innovation. For example, the vacuum cleaner modification would not have been invented had I not been familiar with the basics of physics,” Keinänen notes.

Tero Joronen agrees. He says that inventing is 10% brainstorming and 90% experimentation, the application of knowledge and hard work.

“Creativity is often associated with artistic occupations, but I find that pursuing a career in engineering also requires a great deal of creativity. Creativity is about rethinking the basics of engineering sciences to create something new,” Joronen says.

Your idea has already been invented – so keep working!

All three are familiar with the painful disappointment of coming up with an amazing idea only to discover that it already exists. So many great things have already been invented.

“There is a limit to the amount of information the brain can store. When being hit with a brainwave, one cannot be aware of all the information that is, for example, available online. I sometimes wonder why all the great ideas out there are not being exploited to their full potential. But we have to keep working and pushing the boundaries,” Tamminen says.

The number of patents illustrates the level of commercial awareness in a university.

Being in the zone is a sign that a breakthrough is close

The journey from an idea to an invention depends on the inventor. During a typical workday, Ilmari Tamminen switches between studying biomedical stains and imaging, thinking and testing. He combines his theoretical knowledge and scientific expertise with observations and thinking outside of that famous box.

“I compare my ideas to the existing body of knowledge and move from there,” Tamminen describes.

The theories will either work or not, but it is Nature that decides the outcome, not anyone’s opinion.

“There is this exhilarating moment of discovery when you witness a hypothesis coming to life in a test tube,” Tamminen adds.

All the three inventors inherited their inventive streak, but the ability to see the world from a different perspective can also be learned. Tero Joronen’s method of choice is to tune his mind to a specific frequency.

“As comical as this may sound, it is almost a trance-like state. I close off the outside world to create imaginary visions and try to see beyond the ordinary. Inventing is more about intuition than analytical thinking, but a useful result depends on an interplay between analysis and creativity,” Joronen says.

Women are not inventors, or are they?

The gender gap in patenting reflects the educational and career choices of men and women.

“As a whole, there are more men in the world of inventing,” Olli Sievänen says.

According to the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), 16.5% of inventors named in patent applications were women in 2020. In the past 20 years, the number of patent applications that name at least one female inventor has increased from 20% to 35%.

Biotechnology, chemistry and new drug development are the sectors with the highest proportion of female inventors. More than 59% of the patents related to these fields have at least one female inventor.

The design of mechanical components and engines was at the bottom of the list, with less than 18% of patents having at least one female inventor. Overall, one in four patents is granted to women.

“There are more men working in technology and engineering, and the majority of patent applications are related to these fields. For example, construction engineering and IT are both male-dominated and patent-active sectors in Finland,” Sievänen says.

An invention does not equal important research.

The chances of being issued a patent largely depend on one’s field of research. It is not about supremacy or the degree of creativity and ambition.

“Patents are granted to inventions that can be utilised and scaled up to industrial proportions,” Pasi Keinänen says.

“Breakthroughs and new ways to conduct research are being continuously discovered by social scientists. And while it is incredibly difficult to obtain patent protection for an effective new psychological treatment, it can greatly help large numbers of people and also generate new business,” he adds.

Patents are a barometer for academia

Innovation activities are geared towards making money in the corporate world, but an innovation-oriented approach should also be increasingly embraced in academia, Pasi Keinänen finds. If researchers lack commercial awareness, their inventions may not be placed in the public domain to benefit others.

“Patents are like a barometer for the academic world. The number of patents illustrates the level of commercial awareness in a university. In this respect, the Nordic countries are lagging behind Central Europe,” Keinänen says.

Broadly speaking, the innovation activities of universities are about reconciling academic values with industry needs and sharing world-class Finnish expertise with the rest of the world. Innovative companies need professionals with an innovative mindset.

Tamminen points out that inventions cannot be used for assessing the importance of research. However, an invention can be both a scientific discovery and a commercial success.

“An invention could function as a confirmation of quality and relevance if someone is willing to pay for the results of scientific thinking. This type of integrated career would be my all-time invention,” Tamminen says.