The question of who should get credit for inventing the lightbulb is deceptively complex, and reveals several aspects of the history of science and technology worth revealing. Most people would probably answer the question – Thomas Edison. However, this is more than just overly simplistic. It is arguably wrong. This question has also become political, made so when presidential candidate Joe Biden claims that a black man invented the lightbulb, not Edison. This too is wrong, but is perhaps as correct as the claim that Edison was the inventor.

The question itself betrays an underlying assumption that is flawed, and so there is no one correct answer. That is really what people are referring to with Edison – not that he invented the lightbulb but that he brought the concept over the finish line to a marketable product. Edison sort-of did that, and he does deserve credit for the tweak he did develop at Menlo Park. Instead, we have to confront the underlying assumption – that one person or entity mostly or entirely invented the lightbulb. Rather, creating the lightbulb was an iterative process with many people involved and no clear objective demarcation line. However, there was a sort-of demarcation line – the first marketable lightbulb.

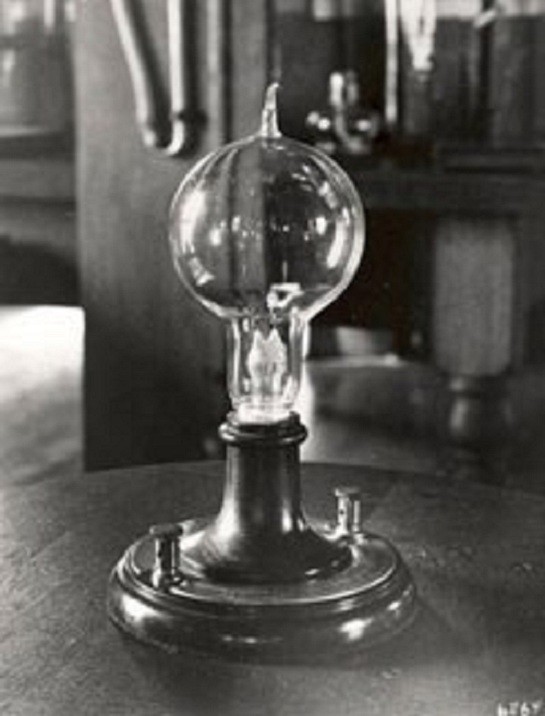

The real story of the lightbulb begins in 1802 with Humphrey Davy He developed an electric arc lamp by connecting Volta’s electric pile (basically a battery) to charcoal electrodes. The electrodes made a bright arc of light, but it burned too bright for everyday use and burned out too quickly to be practical. But still, Davy gets credit as the first person to use electricity to generate light. Arc lamps of various designs were used for outdoor lighting, such as street light and lighthouses, and for stage lighting until fairly recently.

In 1841 Frederick de Moleyns received the first patent for a light bulb – a glass bulb with a vacuum containing platinum filaments. The bulb worked, but the platinum was expensive. Further, the technology for making vacuums inside bulbs was still not efficient. The glass also had a tendency to blacken, reducing the light emitted over time. So we are not commercially viable yet, but all the elements of a modern incandescent bulb are already there. The technology for evacuating bulbs without disturbing the filaments improved over time. In 1865, German chemist Hermann Sprengel developed the mercury vacuum pump, which was soon adopted by lightbulb inventors.

In 1874 Henry Woodward and Mathew Evans filed a patent in the US and Canada for an incandescent bulb with a carbon filament. This seems to have been a commercially viable lightbulb, but the company did not sell well and eventually they sold their patent to Edison. Soon after that, in 1878 William E. Sawyer and Albion Man received a US patent for an incandescent bulb filled with nitrogen with a now familiar zigzagging emmiter. The bulb worked well, but the rigid design made it vulnerable to cracking.

At this point all the basic elements of a modern incandescent bulb are in place. Edison developed none of them. But still the bulb had limitations that prevented it from being commercially viable. It should also be noted that commercial viability was also limited by the batteries of the time and the vacuum technology. Once electrification and a practical way to evacuate a glass bulb existed, the lightbulb was ripe. This is where both Edison and Swan (a British inventor) come it.

Joseph Swan developed his own version of the incandescent bulb, with an evacuated bulb, platinum lead wires, and carbon light-emitting filaments. However, his design still had problems. The carbon filaments were thick and required lots of juice to heat up and glow. Still, Swan receive a patent in the UK for this design in 1879, and in 1881 developed his own lighting company, with improvements on his original design.

At around the same time, Edison was working on his version of the lightbulb. His innovation was to use a thin carbon filament with high electrical resistance. He eventually settled on a carbonized bamboo filament – really his primary technological contribution to the invention of the commercial lightbulb. Edison patented his innovations, and went on tour making sure to align his name with the invention of the lightbulb as much as possible. Swan and Edison eventually sued each other for patent infringement – and Swan won. So legally, one might argue that Swan invented the commercial lightbulb. Edison’s solution was to partner with Swan, forming a joint company, and then totally buying out Swan several years later. So Edison acquired the patents for the lightbulb from others as much as he earned them himself.

Edison does get credit for popularizing the electric lightbulb, and for connecting this to public electricity generation and distribution. Once he had all the patents, his company continued to iterate and improve the technology. This is also where Biden’s “black man” comes in. He was referring to Lewis Howard Latimer. Latimer received a patent in 1882 for a process for improved production of carbon filaments for lightbulbs. Latimer then went to work for the Edison Electric Light Company. Latimer made a significant contribution to the manufacture of lightbulbs, but he didn’t “invent” the lightbulb by any stretch, and is at best a footnote on this interesting history.

While Edison’s contribution to the lightbulb was significant, he did not “invent” the lightbulb. At most he put the last piece into place, acquired any competing patents, and then marketed himself as the inventor. This strategy worked.

But like many stories of both technological and scientific progress, many people contributed over time, and it is not even possible to give credit to any single person.